Being the Wedge: Opening the Door to Lasting Change

Funding Tools Offer Social and Financial Return

On her 100th birthday, Fanny Dotson walked into Hope Credit Union and opened her very first bank account. For Dotson — and The Kresge Foundation — it was a milestone to celebrate.

Dotson had lived an entire century in the Mississippi Delta without ever having a relationship with a bank, therefore missing out on basic wealth-building opportunities many Americans take for granted. Today, she’s among 30,000 members of Hope Credit Union, thanks in part to The Kresge Foundation’s Social Investment Practice.

The Social Investment Practice works alongside Kresge’s program teams to use funding tools that offer both financial and social return to help the foundation create opportunities for low-income people in America’s cities.

Through social investing, Kresge makes bold, nontraditional investments and leverages its capital in ways that encourage other investors — financial institutions, fellow philanthropists, the public sector and other nonprofits — to fund projects that drive social change.

The deals are often complex and include many moving parts, multiple players with varying interests and goals and financing elements that can include low-interest loans, tax credits, equity investments, social impact bonds and more. The deals can take a long time to cross the finish line, and they require a different set of skills than what many foundations cultivate.

But according to Kimberlee Cornett, Kresge’s Social Investment Practice managing director, these investing tools are fueling a revolution in how philanthropy thinks and behaves.

“Almost every big social problem needs a better strategy to achieve long-term change,” Cornett says. “Homelessness, poverty, a broken education system — these complex social problems are unlikely to be solved with grants alone. Through social investing, we’re finding ways to complement grantmaking and play an influential role in driving needed capital to underserved populations.

“We hope we are making social change that will last.”

Moving the Needle

The foundation’s social investing approach began with a few simple loans in 2008. It was bolstered when Cornett was hired in 2010 to head the practice.

Over the next five years, little by little, a social investing culture began to spread through the foundation. Staff were familiar and comfortable pursuing the foundation’s mission through the traditional tools that remain imperative to how Kresge works — from traditional grantmaking to convening, policy work, advocacy and bringing sectors together at one table. Adding social investing tools to the toolbox required an internal shift and new understanding for program teams to envision how loans, guarantees and other financial instruments might support their grantees and work in tandem with grants.

Fast forward to today, and the foundation has made social investments in all of its programs: Arts & Culture, Detroit, Education, Environment, Health and Human Services.

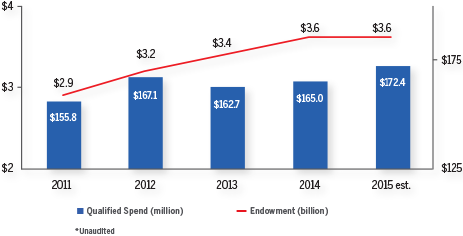

The practice got a big boost in 2015, when the foundation’s Board of Trustees approved a $350 million pool for social investments, a commitment that represents about 10 percent of the foundation’s endowment. The board’s mandate: Put the resources to work by 2020 and leverage $1 billion from other investors.

“By defining this funding pool, we are extending our hand to for-profit and nonprofit partners alike and are asking them to join us on the front lines to use more innovative approaches to this work,” says Kresge President and CEO Rip Rapson.

Kresge approved nine new social investments in 2015, adding to more than 35 active projects so far. Together, those investments have spurred more than $113.5 million from other investors.

Kim Dempsey, Kresge’s deputy director of social investments, has a big vision for the possibilities: new models, thought leadership, heightened risk-taking and increased creativity in how Kresge impacts communities.

“Permanent change comes about by changing markets, behavior and policy,” she says. “We are using capital differently to get to those top-level change factors and to move the needle on some of our country’s most challenging problems.”

Kresge Foundation Social Investment Officer Aaron Seybert says money normally flows along well-worn pathways in the world of finance. Through its work, Kresge aims to carve new grooves in the landscape, funneling the stream of capital toward those who need it most.

“We want to move that pool of money to serve low-income people in American cities,” he says. “To drive social change, Kresge can take the kind of risks that traditional financial institutions don’t.”

In the case of Hope Credit Union, which is headquartered in Jackson, Miss., and serves 55 counties and parishes in the mid-South, Kresge pledged a 10-year, low-interest loan of up to $3 million, provided that Hope matches the funds with $1.5 million in secondary capital.

Ed Sivak, executive vice president for policy and communications at Hope Enterprise Corp., says social investment funding ultimately finds its way to residents who don’t have a bank account or who have little savings. Dotson is one of the many examples that stand out.

“To me, Fanny’s story speaks volumes on a number of fronts,” Sivak says. “It shows the lack of attention commercial banks pay to people like her, and underscores the faith and trust communities have in organizations like Hope.”

Hope’s ultimate goal is to break the cycle of persistent poverty throughout the region by providing checking and savings accounts, along with low-interest car loans and mortgages, to people other banks deem too high-risk.

“We connect people to the financial mainstream with high-quality services,” Sivak says. “Kresge made a substantial long-term investment in Hope at a low cost to us, allowing us to expand our membership and go into places no one else is going.”

Sivak tells of loaning a young woman $1,000 for uniforms and equipment to pursue her dream of becoming an Arkansas state trooper; helping a man purchase his first home so he could care for his granddaughters; and working with a young entrepreneur to expand his pest control business.

Such seemingly small investments have a big impact on the community, Sivak says.

“We have the ability to meet people where they are, and spend the time to improve their situation,” Sivak says. “None of these examples allow us to make a lot of money, but they allow us to make a difference.”

Rays of Light

On the East Coast, Kresge is helping Boston, Mass.-area families avoid foreclosure and stay in their homes. Among them is the Robles family, with three generations under one roof.

The Robles were already locked into a high-interest mortgage they could barely afford when they encountered unexpected medical costs as their daughter went through a difficult pregnancy. When they fell behind on their payments, Stabilizing Urban Neighborhoods (SUN) Mortgage stepped in to help.

Now funded in part by a $2.5 million Kresge social investment, the subsidiary of community development financial institution Boston Community Capital (BCC) was formed in 2009 to help families facing eviction. According to Jessica Brooks, senior vice president of development and communications for SUN Mortgage, BCC had made great strides over 30 years creating communities for low-income residents to find access to good schools, groceries, greenspace and health care services. Then the foreclosure crisis hit in 2010.

“When the housing bubble burst, we saw a bunch of the gains that we and our partners in the community fought so hard for being eroded,” Brooks says.

SUN studied the problem and found that many families — like the Robles — were one paycheck away from losing control of their mortgage. Divorce, family illness or a flat tire could ultimately lead to another abandoned home. An innovative solution that would allow at-risk homeowners to avoid foreclosure and remortgage in a unique way was needed. That’s where SUN comes in.

“We work with homeowners to understand what they can pay, then underwrite them really conservatively,” Brooks says. “We’ll go out to their banks and offer to purchase the property at current distressed market value, then we sell it back the very same day to the homeowner.”

In this way, residents are no longer underwater, and they obtain traditional 30-year mortgages in line with their income. The loans come with a built-in safety net in the form of a capital reserve savings account.

With help from SUN, the Robles were able to stabilize their growing family and reduce their mortgage payments by 63 percent.

Of the 480 mortgages SUN has restructured, delinquency rates are low and defaults are at 7 percent — much lower than the 52 percent average in federal home loan modification programs.

Brooks credits Kresge with encouraging SUN to think outside the box in order to make the most impact.

“Kresge has helped us get financing from other organizations, high-income individuals and federal funding as well,” Brooks says. “It’s clear that they want to be a leader and partner in this type of investing, and we are so grateful for their creativity, their patience, their flexibility and willingness to work with us every step of the way.”

Long-Term Relationships

Kresge can afford to take the long view when it comes to its work, Cornett says. While some grant relationships end after only one year, social investing relationships can span up to a decade or more and sometimes include social or financial benchmarks that must be met along the way.

Take the Strong Families Fund (SFF), a joint pay-for-success effort by Kresge and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation that provides capital to developers of affordable housing who intend to provide wraparound social services as part of their projects. The 10-year pilot aims to show how capital can be used to pay for services that contribute to housing stability and family well-being.

SFF is expected to finance up to seven low-income housing projects that will offer up to 700 units in all. What’s different about SFF is that developers of its projects hire a social services coordinator to be on-site and provide support to residents in areas that include health and wellness, housing stability and education.

Each coordinator builds relationships with residents and becomes the go-to contact when families need help. Data will also be collected to assess the long-term impact of having such support available.

“The idea is that this is an individual who’s trained in engaging residents in housing and has access to services within the community,” says Deborah De Santis, president and CEO of the Corporation for Supportive Housing, which oversees SFF. “Incentives are built into the financing structure. If developers hit certain benchmarks, then they will receive performance payments.

“We believe that by having the metrics and tracking the outcomes, we’ll be able to demonstrate the positive impact. We can then use that from the advocacy standpoint to show that service coordinators need to be funded in affordable housing for families.”

Kresge has committed a total of $6 million to SFF, including its Human Services team authorizing $1.25 million in grant funding and the rest coming from the Social Investment Practice. In total, Kresge and partners including other philanthropic organizations and banks have pledged more than $70 million to the initiative.

Deborah Strong Housing in Ypsilanti, Mich., is the first project to receive funding through SFF. Renovations of its 112 units are in progress.

“This fund is a great example of the bold, innovative approaches that philanthropy and the private sector can use to create positive change,” says Rapson. “Bringing together so many strong partners allows us to marshal shared resources around a common agenda, and achieve a greater impact than any of us can have by going it alone.”

Measuring Outcomes

Another social investment-funded project is bringing health care into low-income residential developments in Colorado. Colorado Coalition for the Homeless (CCH), also a grantee of Kresge’s Human Services team, used a low-interest loan to help build 300 housing units for homeless people in the Denver area. The recently completed Stout Street Lofts, with 78 apartments on its upper floors and a health care clinic below, is among them. The development was fully leased in five weeks and has maintained full occupancy since.

While residents move in directly from the streets, housing isn’t their only concern. Many also face serious physical and mental health issues.

“One gentleman lost both legs to frostbite living on the streets in a wheelchair,” says John Parvensky, CCH president.

Another resident suffers from diabetes as well as mental health issues that make it challenging for her to keep on top of her health.

“Now there’s no excuse not to see the doctor for her monthly checkup because he’s located just downstairs,” Parvensky says. “In fact, the doctor often goes upstairs to knock on her door and check, just to see if everything is OK.”

The integrated approach not only breaks down the barriers to access, but also improves the lives of residents as well as others in the neighborhood who are welcome to use the on-site clinic, pharmacy, dentists, optometrists and counselors.

Parvensky is convinced the integrated model is on the leading edge of health care reform, and he credits Kresge with having the vision to help make it happen.

“Kresge provided us with working capital that allowed us to take some risks and do something we wouldn’t otherwise do,” Parvensky says. “Training staff, equipping a health center and planning an integrated model might have taken much longer to achieve.

“It’s also helping us invest in staff and systems like electronic health records that bridge medical and mental health, housing and social work realms.”

Results are encouraging so far. Of the nearly 10,300 patients served by the Stout Street Health Center, 50 percent expressed a significant decrease in depression symptoms, and 45 percent experienced an improvement in overall health. Nearly 89 percent of families and 88 percent of individuals have kept their apartments for a minimum of two years.

Kresge will forgive some or all of the interest if CCH is able to meet agreed-upon social and health outcomes.

“The focus on measuring the outcomes and providing the incentives to make sure those outcomes are achieved, I think, are the hallmarks of the social investment approach,” Parvensky says.

Meeting Needs

One important role social investments can play is providing proof of concept. When trying new approaches or untested models, things don’t always go exactly to plan. If data show that projects aren’t working or need to change course, social investors like The Kresge Foundation have the temperament to work through those issues.

Roca illustrates that. The Massachusetts-based organization works to help young women and men get off the streets, stay out of jail, obtain good jobs and create a better future for themselves. Kresge partnered with a number of organizations to award Roca a $1.3 million, seven-year social impact bond.

In the social impact bond model, the private sector partners with the public and philanthropic sector to fund critical prevention-focused social programs that address complex, intractable problems. Investors are repaid only if they can prove desired social outcomes are achieved.

If benchmarks are met, the state of Massachusetts will pay back the loan with money saved from building jail cells and housing inmates.

Meeting those benchmarks isn’t easy. Roca is working with an extremely challenged population — mostly men, ages 17 to 24, who have served time for felonies and have very little education or employment history. They are often involved with violent gangs and drugs.

“These are kids who have made very bad mistakes, who have not seen a lot of positive options in their lives,” explains Lili Elkins, Roca’s chief strategy and development officer. “Our job is to look after them and encourage them to come in over and over again until they start to show up on their own and start to change their behavior.”

When program leaders weren’t meeting targets for referrals for getting men into their building, the project faced a critical moment.

The project funders, including Kresge, restructured the financial elements of the deal to give Roca more time to meet its referral targets. The partners also empowered Roca to change its approach as needed to best reach the desired outcome. That meant going out in the community — on street corners, at local hangouts, wherever Roca could track down its target population. Elkins says such relentless outreach is often the only way to help — and ultimately reduce recidivism and turn the men into productive members of society.

“If we need to tweak the model, we have the flexibility to do that in a way that other, more traditional funding might not give us,” Elkins says. “And that’s been really great.”

Ultimately, Roca spends two years with each individual, providing substance abuse counseling, life skills education, GED resources, job readiness training and court compliance assistance.

“Our program is for people who are not yet ready to consider behavior changes,” Elkins says. “It’s designed for the guys who don’t believe they need to change their lives.”

But through Roca, backed by creative financing, they are doing just that.

Social Investment Practice

Kresge's Social Investment Practice works alongside the foundation's program teams to fund projects that drive social change.